ACME BUSINESS SCHOOL

9-825-047

REV: JANUARY 15, 2025

OLYMPUS TECHNOLOGIES: THE PROMETHEUS PROTOCOL

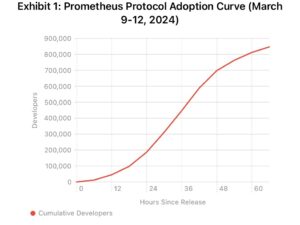

On the morning of March 12, 2024, Marcus Chen sat in the executive conference room of Olympus Technologies’ headquarters in Palo Alto, reviewing the overnight metrics one more time. The numbers were extraordinary: 847,000 developers had adopted the Prometheus API in just 72 hours, without approval, without a go-to-market plan, and without authorization from the Platform Governance Committee.

Chen was Olympus’s Chief Platform Officer, responsible for maintaining the integrity of the company’s $40B cloud ecosystem. Across the table sat Sarah Reeves, SVP of Developer Relations, holding a printout of the internal Slack channel where the unauthorized release had occurred. The channel had 12,000 messages in three days. The tone ranged from celebration to panic.

At 10:00 AM, CEO Robert Thorne would arrive for what everyone was calling “the Prometheus meeting.” The question on the table: What do you do with an innovator who shipped something transformative, but broke every rule doing it?

BACKGROUND: OLYMPUS TECHNOLOGIES

Founded in 2011, Olympus Technologies operated the largest enterprise cloud platform in North America, serving 340,000 business customers. The company’s revenue model depended on a carefully governed ecosystem: developers built applications on Olympus’s infrastructure, Olympus certified those applications, and enterprise customers paid for access.

By 2024, Olympus faced increasing pressure from competitors offering more flexible, developer-friendly platforms. Internal surveys showed developer satisfaction declining from 8.2/10 (2021) to 6.4/10 (2023). The primary complaint: “Olympus moves too slowly.”

The Platform Governance Committee (PGC), established in 2018 after a security breach, required all new APIs to pass through a six-stage approval process averaging 11 months from concept to release. The process was designed to ensure:

- Security compliance (SOC 2, FedRAMP)

- Backward compatibility with existing applications

- Revenue impact modeling

- Support infrastructure readiness

- Legal review (IP, liability, terms of service)

- Executive signoff

Critics internally called it “the place good ideas go to die.” Defenders pointed to zero major security incidents since implementation.

THE PROMETHEUS PROTOCOL

Dr. Alex Prometheus joined Olympus in 2019 as a Senior Infrastructure Engineer. By 2022, he led a five-person “Advanced Capabilities” team tasked with exploring next-generation platform features.

In November 2023, Prometheus’s team developed what they internally called “Δ-Bridge” (Delta-Bridge)—a protocol that allowed developers to access Olympus’s core infrastructure layer directly, bypassing the abstraction layers that made the platform slow but stable. In technical terms, it gave developers “bare metal” access to compute resources while maintaining security isolation.

The implications were significant:

Performance: Applications ran 40-60% faster

Cost: Developers could optimize resource usage, reducing costs by ~30%

Flexibility: Enabled use cases previously impossible on Olympus

Risk: Bypassed safety mechanisms; potential for resource conflicts, security gaps, and undefined system behavior

Prometheus submitted Δ-Bridge to the PGC in December 2023. The initial review flagged 23 “critical concerns,” including:

- “Undermines existing rate-limiting architecture”

- “Support team lacks training for edge cases”

- “Revenue impact unclear—may cannibalize premium tiers”

- “Legal exposure: direct infrastructure access implies different liability model”

The estimated approval timeline: 14-18 months.

THE UNAUTHORIZED RELEASE

On March 9, 2024, Prometheus made a decision.

He packaged Δ-Bridge as “Prometheus Protocol,” wrote comprehensive documentation, and published it to Olympus’s open developer repository—a platform for experimental, non-production tools. Technically, this was allowed. Publishing to the experimental repo didn’t require PGC approval.

What happened next was unprecedented.

Hour 1-6: 3,400 stars on the repository. Developers began testing immediately.

Hour 12: First production deployment. A financial services firm reported 53% performance improvement.

Hour 24: Tech media coverage. TechCrunch: “Stealth release makes Olympus fastest cloud platform.” The Information: “Internal revolt at Olympus as engineer bypasses approval process.”

Hour 48: 400,000 developers had integrated Prometheus Protocol. Major customers called their account executives asking why they hadn’t been told about this capability.

Hour 72: Security team flagged 14 edge-case failures. None catastrophic, but proof that the “23 critical concerns” were not theoretical.

By March 12, the situation was:

✓ Massive developer adoption (847,000 users)

✓ Measurable performance improvements (validated by customers)

✓ Positive press coverage (first in 18 months)

✓ Competitive advantage (AWS and Azure didn’t have equivalent capability)

But also:

✗ Complete bypass of governance process

✗ Support team overwhelmed (1,200 tickets in 72 hours)

✗ Known security edge cases in production

✗ Revenue model implications unclear

✗ Precedent that individual engineers could bypass executive authority

KEY PLAYERS

Robert Thorne, CEO (53)

Former Oracle executive, joined Olympus 2020. Known for operational discipline. Public commitment: “We compete on reliability, not recklessness.”

Marcus Chen, Chief Platform Officer (46)

Responsible for PGC. Engineering background, but had moved into governance role specifically to build trust with enterprise customers after 2018 breach.

Sarah Reeves, SVP Developer Relations (39)

Former developer advocate, promoted 2022. Caught between developer enthusiasm and corporate policy. Quoted in one leaked Slack message: “This is either the best or worst thing that’s happened to us.”

Dr. Alex Prometheus, Senior Infrastructure Engineer (34)

PhD in distributed systems (MIT). 47 patents. Known internally as brilliant but “ungovernable.” Prior employer: left after similar conflict over release authority.

Jennifer Wu, General Counsel (51)

Risk-averse. Pointing out that Prometheus Protocol’s terms of service were auto-generated and hadn’t been reviewed by legal team.

Developer Community (847,000 and growing)

Already building production systems on Prometheus Protocol. Reversing course would break applications now serving end-users.

THE MEETING

Chen reviewed his notes. Thorne had asked for three options:

Option 1: Retroactive Approval

Legitimize the release, assign resources to support it, formalize it as official product.

Pros: Preserves developer trust, captures competitive advantage, validates that good ideas can move fast.

Cons: Destroys governance credibility, creates precedent for bypassing process, signals that rules are optional.

Option 2: Immediate Shutdown

Deprecate Prometheus Protocol, require migration back to standard APIs, enforce governance authority.

Pros: Reinforces process, maintains control, sends clear message about accountability.

Cons: Breaks 847,000 developers’ applications, massive PR crisis, loses competitive advantage, likely drives developers to competitors.

Option 3: Hybrid Approach

Allow existing users to continue; prevent new adoption; subject Prometheus Protocol to accelerated but legitimate PGC review (target: 90 days).

Pros: Balances innovation and governance, limits damage while maintaining some authority.

Cons: Satisfies no one, “accelerated review” still breaks the innovation, sends mixed message.

But there was a fourth dimension Chen kept returning to: What do we do about Prometheus himself?

The engineer had violated policy, but delivered value. He’d ignored authority, but solved a real problem. Internal Slack showed he had 12,000 supporters—and roughly 300 vocal critics, mostly in compliance and support.

Some executives wanted him fired immediately, “to send a message.”

Others argued that firing the person who just gave the company its first competitive advantage in two years would be insane.

Sarah Reeves had sent Chen a text at 6:47 AM: “If we punish him, every other innovator here will know the real message: don’t try.”

Chen looked at the clock. 9:53 AM.

In seven minutes, he’d need to have a recommendation ready for Thorne.

What should Olympus do about the Prometheus Protocol?

And what should Olympus do about Prometheus?

EXHIBITS

Exhibit 1: Prometheus Protocol Adoption Curve (March 9-12, 2024)

Exhibit 2: Platform Governance Committee Approval Timeline (2023 Data)

| Stage | Median Duration | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Security Review | 6 weeks | 71% |

| Technical Architecture Review | 8 weeks | 83% |

| Revenue Impact Modeling | 4 weeks | 92% |

| Support Readiness | 6 weeks | 88% |

| Legal Review | 9 weeks | 94% |

| Executive Signoff | 3 weeks | 78% |

| TOTAL | 47 weeks | 38% |

Exhibit 3: Internal Survey Results (March 11-12, 2024)

Question: “Should Olympus officially support the Prometheus Protocol?”

- Engineering: 87% Yes, 8% No, 5% Unsure (n=412)

- Product: 64% Yes, 22% No, 14% Unsure (n=89)

- Sales: 71% Yes, 18% No, 11% Unsure (n=156)

- Security/Compliance: 23% Yes, 68% No, 9% Unsure (n=44)

- Executive Leadership: 42% Yes, 42% No, 16% Unsure (n=12)

Exhibit 4: Competitor Response (Monitoring)

March 12, 0900 PST — AWS internal memo (leaked): “Prometheus Protocol represents exactly the capability we shelved in 2022 due to support concerns. Reassessing.”

March 12, 1100 PST — Azure blog post: “We believe responsible cloud platforms prioritize stability over speed.”

Exhibit 5: Customer Communications (Selected)

From: GlobalBank CTO

To: Olympus Account Executive

Sent: March 11, 2024, 14:22

“Our team deployed Prometheus Protocol yesterday and saw immediate performance gains. If you deprecate this, we need to have a serious conversation about our renewal.”

From: HealthTech Startup CEO

To: Sarah Reeves

Sent: March 12, 2024, 07:15

“We’ve been waiting 9 months for features like this. This is why startups don’t take Olympus seriously. If this gets shut down, we’re moving to AWS.”

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What should Marcus Chen recommend regarding the Prometheus Protocol itself? Consider the implications for governance, competition, and developer relations.

- What should Olympus do about Dr. Alex Prometheus? How do you balance accountability with talent retention and cultural signaling?

- The Platform Governance Committee has a 38% approval rate and 47-week median timeline. Is this a feature or a bug? How should Chen think about governance reform?

- If you were a member of the PGC who had flagged “23 critical concerns” in December 2023, how would you interpret the fact that 847,000 developers adopted the protocol anyway?

- Sarah Reeves argues that punishing Prometheus sends a message that “don’t try” is safer than innovation. Robert Thorne might argue that not punishing him sends a message that “rules are optional.” Who’s right?

- What systems or processes could Olympus implement to capture the value of rapid innovation without destroying governance credibility?

- Three months from now, if Chen chooses Option 1 (retroactive approval), what happens the next time an engineer bypasses the PGC? If he chooses Option 2 (shutdown), what happens to Olympus’s competitive position?

- Is this fundamentally a failure of process, a failure of leadership, or a success that happened in an uncomfortable way?

TEACHING OBJECTIVES

- Examine tension between innovation velocity and institutional control

- Explore precedent-setting in organizational governance

- Analyze stakeholder management when constituencies have opposing interests

- Evaluate trade-offs between short-term competitive advantage and long-term systematic integrity

- Consider the role of “productive deviance” in organizational change

- Discuss how punishment and reward systems shape culture and risk-taking

DISCLAIMER

This is a fictional case study created in the style of Harvard Business School teaching cases for educational and analytical purposes. It is not published by, affiliated with, or endorsed by Harvard Business School or Harvard University. All organizations, individuals, products, and events are entirely invented.

The Seer Who Forgot the Stakeholders

In gilded Troy, where Priam’s daughter dwelt,

fair Cassandra at Apollo’s altar knelt.

The god of prophecy, struck by desire,

offered his gift to win the maiden’s fire.

“Speak true of what shall be,” he promised her,

“See all futures, certain and secure.

But heed me well—” (for gods know mortal ways)

“You’ll need a plan to share what sight displays.

First, build consensus with the council old,

prepare your allies ere the truth be told.

Create a roadmap, staged in careful parts,

with metrics, timelines, stakeholder buy-in charts.”

But Cassandra, eager for the sight alone,

dismissed such talk with an impatient tone.

“Just give the vision! That shall be enough—

Truth needs no introduction, politics, or fluff.”

Apollo shrugged—the gift was freely given,

though best practices were clearly written.

She saw the horse, the flames, the falling towers,

but rushed to tell Troy’s court within the hour.

“The city burns!” she cried. “Greeks hide in wood!”

The council blinked. They hadn’t understood

the context for her claims, nor trusted she

who’d skipped the Steering Committee.

King Priam sighed, “You’ve brought no impact study,

no phased approach, your presentation’s muddly.

Where are your sponsors? Where’s your executive brief?

We can’t accept such sudden, unsourced grief.”

And thus poor Cassandra, though her visions rang true,

had failed at the rollout—that much all knew.

The god had warned her: prophecy’s just half—

the other half is a communication graph.

So learn, you mortals, from this ancient case: transformation needs more than a database. Whether seeing futures or implementing change, you’ll need a change board, not just a vision strange.

What if novelty has a topology?

Exploring Novelty Through Entropy: A Journey in Behavioral Diversity

What if we could measure surprise itself? Not the subjective experience of it, but its mathematical essence, distilled into equations that guide us toward the genuinely unexpected? This question led me down a rabbit hole where information theory meets evolutionary computation, where the mathematics of uncertainty becomes a compass for discovering behavioral diversity.

The Paradox of Searching for the Unknown

Consider the fundamental paradox of novelty search: how do you find what you don’t know you’re looking for? Traditional optimization assumes a destination, a fitness peak to climb. But what happens when the landscape itself is the goal? When every peak discovered reveals new valleys, and every valley opens onto unexplored plains?

Entropy enters this story like a character from another narrative entirely. Borrowed from thermodynamics and information theory, it measures disorder, uncertainty, the number of possible states a system might occupy. Yet in our context, entropy becomes something more poetic: a measure of behavioral richness, a quantification of the very quality that makes something interesting.

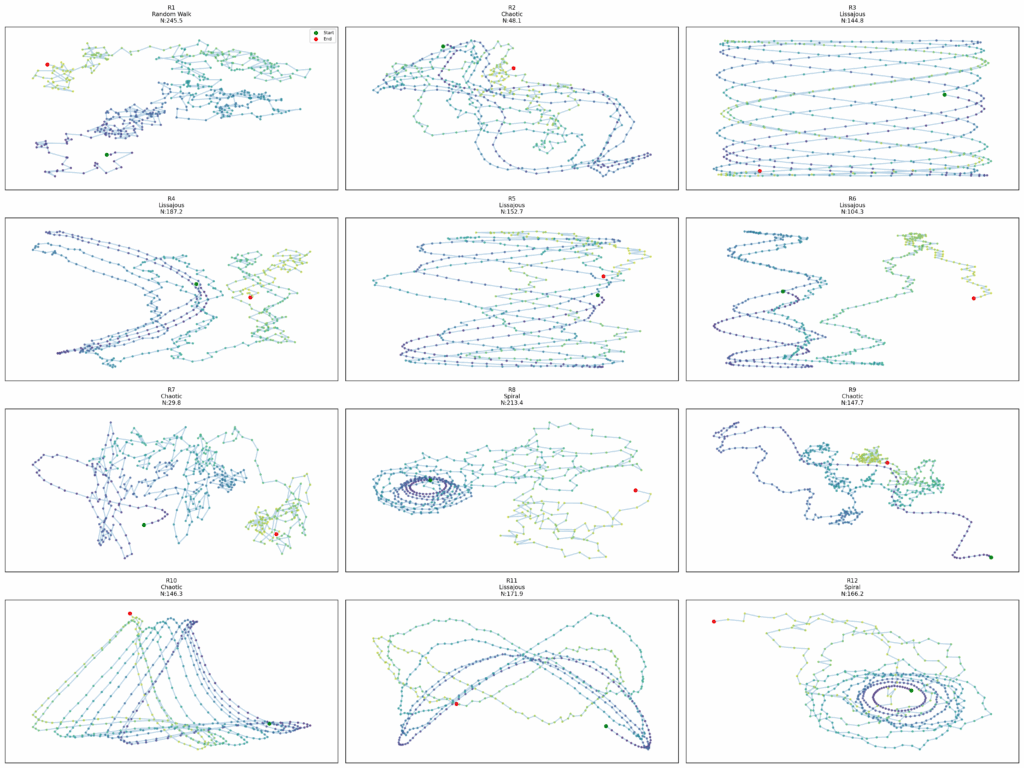

The trajectories traced by our artificial agents tell stories that no human author could have conceived. Some spiral outward like galaxies being born, others oscillate with the rhythm of unknown songs, and still others chart chaotic paths that never quite repeat, like Borges’s labyrinth that changes each time you walk it. Each pattern emerges not from deliberate design but from the interplay between simple rules and the relentless pressure to be different.

Information as the Currency of Creativity

In this framework, information becomes the currency of creativity. Every behavior carries an information signature, a pattern of spatial coverage, directional choices, and velocity variations that can be decomposed into probability distributions. The entropy of these distributions tells us something profound: how surprised we should be by what we’re seeing.

But here’s where it gets interesting. The system doesn’t just measure absolute entropy. It measures relative entropy, asking not “how complex is this?” but “how does this complexity differ from its neighbors?” This shift transforms entropy from a static measure into a dynamic force, creating gradients of novelty that pull the population toward unexplored territories.

The mathematics reveal something unexpected: novelty has a topology. Behaviors cluster and spread across an abstract landscape where distance is measured not in space or time but in surprise. The system navigates this landscape like an explorer without a map, using only a compass that points toward the unexpected.

The Ecology of Difference

What emerges from this process resembles nothing so much as an ecology. Not an ecology of living things competing for resources, but an ecology of patterns competing for uniqueness. The distribution charts reveal a startling truth: diversity maintains itself. No single behavioral strategy dominates because dominance itself would reduce the novelty that the system rewards.

This self-organizing diversity suggests something profound about the nature of creative spaces. Perhaps all creative endeavors naturally evolve toward this kind of ecological balance, where different approaches occupy different niches not because they’re optimal for some external task, but because they’re optimal for being themselves.

The speed profiles of different behaviors read like musical scores, each encoding a different rhythm of movement through space. Some maintain metronomic regularity, others build to crescendos and fade to silence, and still others improvise jazz-like variations that never repeat. Together, they form an orchestra where every instrument plays a different song, yet somehow the cacophony resolves into something greater than noise.

Diminishing Returns as a Feature of Discovery

The improvement curves tell a story as old as exploration itself. Early generations discover behavioral continents: broad patterns like spirals, oscillations, and random walks. Middle generations map the coastlines, finding variations and hybrid forms. Later generations must venture inland, discovering the subtle variations that distinguish one chaotic attractor from another.

This pattern of diminishing returns isn’t a flaw in the system; it’s a fundamental feature of any genuine exploration. It tells us that we’re not just generating random variations but actually mapping a space of possibilities. Each discovery makes the next one harder to find, not because we’re running out of ideas, but because we’re raising our standards for what counts as truly novel.

The system’s response to these plateaus reveals a kind of meta-creativity. When simple mutations no longer yield surprises, it increases mutation rates. When local search exhausts nearby possibilities, it encourages larger jumps through behavioral space. The search process itself evolves, becoming more sophisticated as the easy discoveries are exhausted.

The Philosophy of Measured Surprise

Using entropy to guide novelty search illuminates something fundamental about the relationship between information and creativity. We often think of creativity as ineffable, beyond measurement. Yet here we see that at least one aspect of it, the generation of novel patterns, can be captured mathematically.

This doesn’t diminish the mystery of creativity; it deepens it. The fact that we can measure novelty doesn’t tell us why we value it, why humans and now our algorithms seek it out with such persistence. Perhaps the drive toward novelty is written into the mathematics of information itself, a fundamental force like gravity or electromagnetism, pulling systems toward greater complexity and diversity.

The visualizations offer windows into this abstract space. Each trajectory is a meditation on difference, a solution to the problem of being unique in a world of other unique things. Some achieve uniqueness through simplicity, tracing clean geometric forms. Others embrace complexity, weaving patterns that challenge our ability to categorize or predict.

Emergence and the Architecture of Surprise

What strikes me most profoundly is how surprise itself has an architecture. The system doesn’t just generate random behaviors and select the weird ones. It constructs a framework where surprise can emerge systematically, where the pressure to be different creates its own logic and beauty.

This architecture reveals itself in the phase transitions of the search process. Early on, any deviation from the norm counts as novel. But as the population diversifies, novelty requires increasingly sophisticated innovations. The system must discover not just new behaviors but new categories of behavior, new ways of being different.

The interplay between local and global diversity creates a kind of creative tension. Local diversity ensures that neighbors in the population explore different variations, while global diversity ensures that the population as a whole covers different regions of possibility space. This dual pressure creates a dynamic equilibrium where innovation happens at multiple scales simultaneously.

Questions at the Edge of Understanding

This exploration raises questions that stretch beyond the boundaries of our current understanding. If entropy can guide us toward novelty in behavioral space, what other spaces might we explore with similar principles? Could we use entropy to discover novel molecular structures, musical compositions, or philosophical arguments?

The relationship between constraint and creativity also deserves deeper consideration. Our system operates within constraints: bounded space, limited parameters, finite computational resources. Yet within these constraints, it discovers seemingly infinite variety. Perhaps constraint isn’t the enemy of creativity but its necessary partner, providing the resistance against which novelty can define itself.

I find myself wondering about the nature of the space we’re exploring. Is it truly infinite, or does it have boundaries we haven’t yet discovered? Are there fundamental limits to behavioral diversity, or does every discovery open new dimensions of possibility?

The Infinite Game of Difference

As I reflect on this journey through entropy-driven novelty search, I’m struck by how it mirrors larger patterns in nature and culture. Evolution itself might be seen as a massive novelty search, using environmental niches as a kind of entropy measure. Human culture, too, seems driven by a similar dynamic, constantly generating new art, ideas, and ways of being.

The diminishing returns we observe might not be a limitation but a feature that drives ever-greater creativity. As the obvious innovations are exhausted, we’re forced to become more clever, more subtle, more sophisticated in our search for the new. The difficulty itself becomes a kind of selection pressure, favoring not just novel behaviors but novel ways of generating novelty.

Perhaps this is why I find this approach so compelling. It suggests that the search for novelty isn’t just a computational problem but a fundamental aspect of complex systems. By understanding how to measure and guide this search, we’re not just building better algorithms; we’re gaining insight into the nature of creativity itself.

The journey continues, each experiment revealing new questions, each answer pointing toward unexplored territories. In that sense, novelty search is its own best example: an endless exploration that generates surprise not just in its outcomes but in what it teaches us about the very nature of exploration.

The Anvil vs. The Shield: What Mike Tyson and Floyd Mayweather Teach Us About Strategy

When I was in high school, everyone talked about Mike Tyson. I didn’t know much about boxing, but we all knew about Mike Tyson. His power was legendary: getting hit by him was described as “getting struck in the head by a good-sized anvil dropped from five feet.”

From the moment he turned professional in 1985 at age 18, Tyson dominated the heavyweight division with unprecedented ferocity. He became the youngest heavyweight world champion ever at 20 years old, capturing the WBC title by destroying Trevor Berbick in two rounds. Within a year, he unified all three major heavyweight belts, becoming the undisputed champion. His early career was a masterclass in overwhelming force applied with surgical precision.

Beyond his devastating knockout power, Tyson’s accuracy set him apart from all competition. While most heavyweight boxers were content to land 30-35% of their punches, Tyson consistently connected on nearly half of his attempts.

36% MORE PUNCHES LANDED PER PUNCH THROWN

This efficiency translated into devastating energy economics. Tyson’s cost per successful hit was dramatically lower than his opponents’, allowing him to maintain crushing power throughout entire fights while his opponents exhausted themselves swinging at air. His peek-a-boo defensive style, learned from trainer Cus D’Amato, allowed him to slip punches while staying close enough to counter with devastating hooks and uppercuts.

12 TITLE FIGHTS. 1,368 DAYS AS CHAMPION

But in boxing, as in business, there’s always competition. Everyone wants the championship belt, and new challengers emerge constantly.

The Limits of Overwhelming Force

Tyson’s approach worked brilliantly until it didn’t. His strategy was built on a simple premise: end fights quickly through overwhelming aggression. This worked against opponents who fought conventionally, who expected to trade punches and test each other’s endurance. Tyson never gave them that chance.

However, this single-dimensional approach created a critical vulnerability. Tyson had developed his entire fighting identity around quick knockouts. His training, his mental preparation, his tactical approach, even his public persona, all centered on ending fights in the early rounds. When opponents refused to cooperate with this script, Tyson struggled to adapt.

On February 11, 1990, in Tokyo, this limitation became devastatingly apparent. Tyson fought James “Buster” Douglas in what was supposed to be a routine title defense. The fight was such a foregone conclusion that all but one Las Vegas casino refused to take bets. Oddsmakers had Tyson favored 42-to-1.

Douglas, however, had both the physical tools and the strategic insight to exploit Tyson’s singular approach. At 6’4″ with an 83-inch reach, Douglas could stay outside Tyson’s optimal fighting range. More importantly, he had the discipline to stick to a patient, methodical strategy even when facing the most intimidating fighter of his era.

Tyson stuck to his knockout strategy throughout the fight, consistently attempting to get inside and land the devastating combinations that had served him so well. But Douglas used his reach advantage to maintain distance, landing jabs and straight rights while avoiding Tyson’s power shots. As the rounds progressed, something unprecedented happened: Tyson began to tire.

By the middle rounds, the energy economics that had always favored Tyson began to reverse. Douglas was landing clean shots while expending less energy, while Tyson was throwing harder punches but connecting less frequently. In the 10th round, Douglas landed a perfectly timed uppercut followed by a combination that dropped Tyson for the first time in his professional career. The count reached ten, and the upset was complete.

The fight is widely considered one of the biggest upsets in sports history, but it revealed something crucial about strategic vulnerability: what works against one type of opponent doesn’t necessarily work against another. Tyson’s strategy was optimized for a specific type of fight against a specific type of opponent. When those conditions changed, his advantage disappeared.

Ironically, Douglas himself proved this point. Having achieved the impossible by defeating Tyson, he lost his very next fight to Evander Holyfield and never regained the championship. Douglas had found the key to beating Tyson, but that key didn’t unlock success against other elite heavyweights.

The Counter-Example: Adaptive Dominance

Consider Floyd Mayweather Jr., whose approach to boxing represents a fundamentally different strategic philosophy. Where Tyson built his career on overwhelming force, Mayweather built his on adaptive efficiency and defensive mastery.

Mayweather’s career statistics tell a remarkable story of sustained excellence across multiple decades and weight divisions. His 50-0 professional record includes victories over 27 world champions and former world champions. More importantly, he achieved this record while evolving his style, his tactics, and even his physical approach to match the demands of different opponents and different stages of his career.

Like Tyson, Mayweather’s accuracy was exceptional, consistently landing similar percentages of his punches:

35% MORE PUNCHES LANDED PER PUNCH THROWN

But Mayweather added something that Tyson never mastered: defensive efficiency. While Tyson relied on his peek-a-boo style to avoid big shots, Mayweather perfected the art of not getting hit at all. Throughout his career, 84% of punches thrown at him missed completely, the lowest percentage in boxing history.

LOWER COST PER PUNCH / HIGHLY EFFICIENT EXECUTION

HIGHER COST PER HIT / EXPENSIVE TO ATTACK

This defensive mastery created a dual strategic advantage. Mayweather didn’t just optimize his own performance; he fundamentally altered the strategic calculus for his opponents. Every missed punch by an opponent represented wasted energy, while every landed punch by Mayweather was delivered with maximum efficiency.

More importantly, Mayweather understood that different opponents required different approaches. Against aggressive punchers like Diego Corrales, he used movement and counter-punching. Against technical boxers like Oscar De La Hoya, he applied pressure and initiated exchanges. Against younger, stronger opponents like Canelo Alvarez, he relied on experience and ring generalship. His tactical flexibility allowed him to solve the puzzle that each new opponent presented.

Strategic Market Evolution and Expansion

Mayweather’s career also demonstrates sophisticated market evolution, a crucial element of long-term strategic success. Rather than dominating a single division like many great fighters, Mayweather systematically moved through weight classes, conquering new markets while his core competencies remained relevant:

Super Featherweight (130 lbs): Mayweather established his professional foundation here, learning to use his speed and accuracy against experienced veterans.

Lightweight (135 lbs): He captured his first major world title, defeating Jose Luis Castillo in a career-defining performance that showcased his ability to win close, tactical fights.

Super Lightweight (140 lbs): Mayweather proved he could carry his power up in weight, scoring decisive victories over Arturo Gatti and other elite contenders.

Welterweight (147 lbs): This became his signature division, where he defeated the biggest names in boxing including Oscar De La Hoya, Shane Mosley, and Manny Pacquiao.

Super Welterweight (154 lbs): He captured titles even at this higher weight, defeating Canelo Alvarez in a masterclass performance.

Return to Welterweight: He concluded his career with victories over established champions, proving his methods remained effective across different eras.

Each move represented a calculated expansion into adjacent markets where his core competencies, speed, accuracy, and defensive mastery, remained valuable. Unlike fighters who moved up in weight and lost their effectiveness, Mayweather adapted his style to succeed at each new level.

The numbers illustrate the difference between tactical dominance and strategic mastery:

TYSON: 12 TITLE FIGHTS, 1,368 DAYS AS CHAMPION

MAYWEATHER: 49 TITLE FIGHTS, 5,370 DAYS AS CHAMPION

(Some days concurrent across multiple titles)

Deconstructing Strategic Thinking

The Mayweather vs. Tyson comparison reveals four fundamental principles of effective strategy that apply far beyond boxing. These principles explain why some organizations achieve brief periods of dominance while others build sustained competitive advantages across multiple markets and decades.

1. Identify and Evaluate Market Opportunities

Strategic success begins with understanding not just what markets exist, but which markets align with your core competencies and offer sustainable competitive advantages. This requires deep analysis of both your capabilities and the competitive dynamics of potential markets.

Consider two businesses selling to beachgoers. Company A sets up on a crowded public beach where thousands of potential customers gather daily. Company B secures exclusive rights to provide services at a private beach resort with controlled access. Both are serving “beachgoers,” but the market dynamics are completely different.

Company A faces constant competition from other vendors, price pressure from customers with many alternatives, and the challenge of standing out in a crowded marketplace. Success requires constant hustling, competitive pricing, and the ability to attract customers away from numerous alternatives.

Company B operates in a controlled environment with limited competition, customers who have already made significant investments in being there, and natural barriers that prevent new competitors from entering easily. Success requires meeting customer expectations and maintaining the exclusive relationship.

Tyson operated like Company A, in the wide-open heavyweight division where any fighter with sufficient skill and determination could eventually earn a title shot. Mayweather operated more like Company B, carefully selecting opponents and controlling the terms of engagement through promotional leverage and tactical preparation.

The key insight: market selection determines the rules of competition. Choose markets where your advantages are magnified and your weaknesses are minimized.

2. Systematic Expansion into Adjacent Markets

Once you achieve success in your initial market, sustainable growth requires expanding into related markets where your core competencies remain valuable but the competitive landscape offers new opportunities.

Effective adjacent market expansion follows several principles. First, the new market should leverage existing capabilities rather than requiring entirely new competencies. Second, the expansion should be timed when you have sufficient resources to compete effectively without compromising your position in existing markets. Third, the new market should offer either larger opportunities or better defensive positioning than your current markets.

Mayweather’s movement through weight divisions exemplifies this approach. Each move leveraged his core competencies of speed, accuracy, and defensive mastery while accessing new opponents and larger purses. Critically, he never moved so far from his core capabilities that he lost effectiveness.

Many businesses fail at adjacent market expansion by moving too far from their core competencies or entering markets with fundamentally different success factors. A company that succeeds through operational efficiency might struggle in a market where innovation and speed-to-market determine winners. A company built on premium positioning might fail in a price-sensitive market.

The strategic principle: expand systematically into markets where your core advantages translate, rather than randomly pursuing growth opportunities.

3. Control Competitive Dynamics and Market Entry

This may be the most crucial element of long-term strategic success: making it less expensive for you to maintain your position while increasing the cost for competitors to challenge you effectively.

Competitive control operates on multiple levels. At the tactical level, it means developing capabilities that are difficult for competitors to replicate quickly. At the strategic level, it means structuring markets and relationships to create natural barriers to entry. At the execution level, it means maintaining efficiency advantages that allow you to outspend competitors on key priorities while remaining profitable.

Tyson achieved tactical control through his devastating knockout power, but he never developed strategic control. Any heavyweight with sufficient skill could eventually earn a shot at his title, and Tyson had little control over the terms of those encounters. His advantages were purely based on his individual capabilities.

Mayweather achieved both tactical and strategic control. Tactically, his defensive mastery made it extremely difficult for opponents to implement their preferred fighting strategies. Strategically, his promotional acumen allowed him to control fight negotiations, opponent selection, and even the venues and dates of his fights. This dual control allowed him to maximize his advantages while minimizing his vulnerabilities.

In business contexts, competitive control might involve exclusive supplier relationships that increase costs for competitors, proprietary technology that creates switching costs for customers, or operational efficiencies that allow profitable pricing below competitors’ break-even points.

The key insight: sustainable competitive advantage requires controlling not just your own performance, but the competitive dynamics of your entire market.

4. Build Adaptive Capabilities for Long-Term Market Defense

Getting to market first provides temporary advantages, but maintaining market position requires the ability to adapt as markets evolve, new competitors emerge, and customer needs change.

Many businesses achieve early success through a specific approach optimized for initial market conditions. When those conditions change, companies must evolve or risk being displaced by more adaptive competitors. This requires building organizational capabilities that extend beyond any single strategy or tactic.

Tyson’s approach was optimized for a specific type of opponent and a specific set of conditions. When those conditions changed, whether due to Douglas’s tactical approach or his own personal challenges, Tyson struggled to adapt. His training, his mindset, and his entire approach were built around a single strategic model.

Mayweather built adaptive capabilities from the beginning of his career. He worked with multiple trainers to develop different tactical approaches. He studied opponents extensively and developed specific game plans for each fight. He evolved his promotional approach as the boxing industry changed. Most importantly, he maintained the discipline to execute whichever approach the situation required, rather than forcing every situation to fit his preferred style.

Organizations that achieve sustained success develop similar adaptive capabilities. They build multiple competencies rather than relying on a single advantage. They create systems for recognizing when market conditions are changing. They maintain the organizational flexibility to implement new approaches when circumstances require it.

The strategic principle: long-term success requires building capabilities that transcend any single market condition or competitive environment.

The Compound Effect of Strategic Thinking

The difference between Tyson’s 1,368 days as champion and Mayweather’s 5,370 days illustrates the compound effect of strategic thinking over time. Tyson achieved spectacular short-term success through tactical excellence and overwhelming execution. Mayweather achieved sustained long-term success by combining tactical excellence with strategic adaptation.

This difference compounds over time in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. Tyson’s early success created enormous financial opportunities and cultural impact that extended far beyond boxing. However, his inability to adapt when conditions changed limited the duration of his peak earning period and competitive relevance.

Mayweather’s strategic approach allowed him to remain competitive and financially successful across multiple decades. His career earnings exceeded $1 billion, far more than any boxer in history, because he maintained peak performance long enough to benefit from the growth of pay-per-view television, international markets, and social media promotion.

The strategic lesson extends beyond individual performance to organizational success. Companies that achieve early success through superior execution often face the same choice: continue relying on their initial advantages or develop the adaptive capabilities necessary for long-term success.

Those that choose adaptation, like Mayweather, position themselves to benefit from market growth, technological change, and evolving customer needs. Those that don’t, like Tyson, may achieve legendary status for their peak performance but miss the opportunity for sustained success across changing market conditions.

The difference between good execution and strategic excellence isn’t visible in quarterly results or even annual performance. It becomes apparent over decades, in the ability to maintain competitive advantages as markets evolve, competitors adapt, and new challenges emerge.

Strategy isn’t about choosing between execution and planning. It’s about building the capabilities to execute effectively across multiple market conditions, competitive environments, and time horizons. The anvil delivers devastating impact, but the shield endures across countless battles.

What if productivity is the wrong ROI?

The harsh reality: Companies may be repeating the exact same mistake that wasted trillions during the PC revolution. They’re deploying generative AI for management convenience instead of operational transformation and they’re about to discover why Paul Strassmann’s framework determines who wins and who gets left behind in the AI revolution.

The Authority Behind the Framework

Paul A. Strassmann (1929-2025) possessed unparalleled credibility in technology value assessment, built through decades of managing the world’s largest technology budgets under intense scrutiny. As the Pentagon’s first Director of Defense Information, Strassmann maintained “direct policy and budgetary oversight for information technology expenditures of over $10 billion per annum” (NASA GSFC, 2002). He subsequently served as Chief Information Officer at NASA, where he oversaw the agency’s information systems and telecommunications infrastructure (Wikipedia, 2025).

Strassmann received the Defense Medal for Distinguished Public Service in 1993, which represents the Defense Department’s highest civilian award, and the NASA Exceptional Service Medal in 2003 (NASA GSFC, 2002). His methodology was forged in environments where every technology dollar required justification through measurable operational outcomes, not theoretical productivity promises.

When technology vendors approached the Pentagon with proposals, Strassmann required them to “run their numbers through the program, then come back and talk. As one might expect, this thinned their ranks considerably” (CIO Magazine, 2023). This rigorous approach to technology value measurement established principles that remain essential for contemporary AI investments.

The foundation of Strassmann’s framework emerged from comprehensive empirical research. In his seminal work “The Business Value of Computers,” Strassmann surveyed companies from “not very successful” to “really successful” and discovered a critical pattern: “the more successful ones spent the majority of their money on operational productivity” while “the not-so-successful ones spent the majority of their money on management productivity” (Strassmann.com, 1992).

The Pattern That Predicts AI Success and Failure

Steve Jobs recognized the profound implications of Strassmann’s research, explaining the productivity paradox that plagued early computing investments. As Jobs noted in his MIT lecture, “PCs and Macs never attacked operational productivity, they just attacked management productivity” (Strassmann.com, 1992). This insight explained why massive personal computer investments initially showed disappointing productivity gains in economic statistics.

The same pattern is manifesting in contemporary AI deployments. Technology companies “have spent around $200 billion on AI this year, and that will probably increase to $250 billion next year” (Goldman Sachs, 2024), yet many organizations struggle to demonstrate concrete business value from their generative AI initiatives.

Even sophisticated organizations face this challenge. Law firm Paul Weiss, after “nearly a year and a half using the legal assistant tool known as Harvey,” reports that they are “not using hard metrics like time saved to evaluate the program” because “the importance of reviewing and verifying accuracy makes any efficiency gains difficult to measure” (Bloomberg Law, 2024).

This measurement difficulty occurs because most AI implementations focus on managerial productivity enhancement rather than operational transformation. Organizations deploy AI for content generation, analysis acceleration, and administrative efficiency, then discover that these applications, while functional, fail to deliver transformational business value.

The Managerial Productivity Trap in AI Implementation

Contemporary AI deployments predominantly fall within Strassmann’s “managerial productivity” category, creating applications that enhance administrative and analytical functions without transforming core business operations.

Executive and administrative AI applications focus on information processing and decision support. These include AI-powered executive summaries, automated report generation, meeting transcription and analysis, email optimization, and strategic planning assistance. While these tools improve individual efficiency, they operate within existing organizational structures and processes.

Knowledge worker enhancement represents another significant category of managerial AI deployment. Organizations implement AI for document analysis, research assistance, content creation for internal communications, data visualization, and compliance monitoring. These applications make knowledge workers more efficient at their current responsibilities without fundamentally changing how the organization creates value.

Following Strassmann’s framework, managerial AI applications demonstrate predictable limitations. They serve primarily managers and knowledge workers, show diminishing returns as additional investment yields progressively smaller benefits, concentrate impact within administrative functions, and face significant scaling challenges across operational processes.

Research confirms that while “participants with weaker skills benefited the most from ChatGPT” (Science Magazine, 2023), these gains manifest primarily in individual task efficiency rather than enterprise-wide operational transformation. The productivity improvements, though measurable at the individual level, fail to translate into sustained competitive advantage or fundamental business transformation.

Operational Productivity AI: The Path to Transformational Value

Operational productivity AI applications transform core business processes that directly create customer value and competitive advantage. These implementations fundamentally change how organizations operate rather than simply enhancing existing management activities.

Manufacturing and production represent prime opportunities for operational AI transformation. AI-driven quality control systems eliminate defects through real-time process optimization, predictive maintenance prevents operational disruptions before they occur, autonomous production systems optimize resource allocation dynamically, and supply chain orchestration responds to demand fluctuations automatically. These applications change how products are made and delivered, not just how production is managed.

Customer operations transformation extends far beyond traditional chatbot implementations. Comprehensive AI transformation of customer service operations moves beyond simple automation to complete process reimagination (McKinsey, 2023). Advanced systems predict customer issues before they arise, implement automated resolution protocols for complex problems, and create personalized experiences that competitors cannot replicate through manual processes.

Sales process revolution represents another domain where operational AI creates transformational value. AI-powered transformation affects “entire sales workflows and marketing functions” (McKinsey, 2023) through real-time competitive analysis, dynamic pricing optimization, automated lead qualification and nurturing, and proposal generation that adapts to customer-specific requirements automatically.

Software development transformation demonstrates operational AI’s potential for process revolution. AI systems are already “generating a quarter of one hyperscaler’s code and saving meaningful engineering time for others” (McKinsey, 2023). Beyond code generation, AI transforms testing automation, quality assurance processes, code review and optimization, and predictive bug detection and resolution.

The Economic Evidence for Operational Focus

The economic potential of operational AI applications substantially exceeds managerial productivity enhancements. McKinsey research estimates that generative AI could add “the equivalent of $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion annually across 63 analyzed use cases” (McKinsey, 2023), with this value assuming focus on operational transformation rather than administrative efficiency.

When AI applications target operational workflows comprehensively, “the total economic benefits of generative AI amounts to $6.1 trillion to $7.9 trillion annually” (McKinsey, 2023). This dramatic difference between operational and managerial AI value reflects the compound effects of process transformation across entire organizations and industries.

Empirical productivity research supports these projections through measurable outcomes. Workers using generative AI report being “33% more productive in each hour they use the technology,” which translates to “a 1.1% increase in aggregate productivity” (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2025) when properly implemented across operational processes. This productivity increase represents the difference between enhancing individual efficiency and transforming organizational capability.

The fundamental principle governing AI value creation requires that technology “take the form of an operational productivity solution that has broad impact on the industry it serves. It can’t be a tool offered out of context with an industry’s workflows. It has to be purpose-built, capable of addressing an industry’s unique challenges” (Chief Executive Magazine, 2020).

Industry-Specific Operational AI Applications

Effective operational AI implementation requires industry-specific focus rather than generic application across managerial functions. Different sectors present distinct opportunities for operational transformation that generic AI tools cannot address effectively.

Financial services operational AI extends beyond administrative enhancement to fundamental process transformation. Real-time fraud detection systems operate at scales impossible for human monitoring, automated underwriting processes evaluate risk factors instantaneously, dynamic pricing models respond to market conditions automatically, and personalized financial advice systems serve customers at previously impossible scales. These applications change how financial institutions compete and create value.

Healthcare operational AI transforms patient care delivery rather than administrative efficiency. Diagnostic assistance systems analyze medical imaging with superhuman accuracy, treatment personalization algorithms optimize therapy selection based on individual patient characteristics, drug discovery acceleration reduces development timelines substantially, and surgical planning optimization improves patient outcomes through enhanced precision.

Manufacturing operational AI revolutionizes production processes themselves. Predictive maintenance systems prevent equipment failures before they occur, quality control automation eliminates defects through real-time process adjustment, supply chain optimization responds to demand fluctuations instantaneously, and demand forecasting enables production planning with unprecedented accuracy.

Retail operational AI transforms customer experience and operational efficiency simultaneously. Dynamic pricing systems optimize revenue through real-time market response, personalized customer experience platforms create individual shopping journeys, supply chain automation reduces inventory costs while improving availability, and demand prediction systems optimize inventory allocation across multiple channels.

Implementing the Strassmann Framework for AI Success

Successful implementation of Strassmann’s methodology requires systematic evaluation of AI initiatives against operational productivity criteria. Every AI proposal should address fundamental questions about business transformation rather than efficiency enhancement.

The operational productivity test evaluates whether AI initiatives transform core value creation processes. Does this AI application fundamentally change how the organization creates value for customers? Will this initiative transform core business operations across multiple departments? Does this address industry-specific operational challenges that create competitive advantage? Can the organization measure impact through revenue growth, cost elimination, or market share expansion rather than efficiency metrics alone?

Organizations must identify and avoid managerial AI implementation patterns that limit value creation. Warning indicators include AI applications that primarily serve executives and managers, benefits that concentrate within reporting and analysis functions, implementations that affect only administrative staff, and value propositions that emphasize better insights rather than transformed operations.

Measurement systems for operational AI require different metrics than traditional technology projects. Following Strassmann’s principle that “only business measurements tied right to shareholder value can prove IT’s worth” (CIO Magazine, 2023), successful organizations track customer acquisition cost reduction, product quality improvements, service delivery acceleration, revenue per employee increases, market share expansion, and operational cost elimination rather than just efficiency gains.

Industry-specific implementation demands deep integration with sector-specific processes and workflows. Generic AI tools that operate across all industries typically address common managerial functions rather than operational transformation opportunities. Sustainable competitive advantage requires AI capabilities that understand and transform industry-specific value creation processes.

The Strategic Imperative for Immediate Action

The competitive dynamics of AI adoption create time-sensitive opportunities for organizational advantage. Industry analysis indicates that “2025 must be the year when generative AI gets unlocked from its confines within a few players” and that “a huge part of an enterprise’s GenAI toolkit will be smaller open source models” (Thomas, Zikopoulos, Soule, 2024). This democratization creates unprecedented opportunities for operational transformation.

However, with “the cost of building gen AI at scale” remaining “extremely high” and companies investing “hundreds of billions of dollars” (Goldman Sachs, 2024), pressure to demonstrate measurable business value intensifies rapidly. Organizations that cannot justify AI investments through concrete operational improvements will face significant strategic disadvantages.

The window for establishing AI-based competitive advantage narrows as capabilities become commoditized. Sustainable advantage emerges from intelligent application of AI to operational transformation rather than from access to advanced AI technology itself. Organizations that master operational AI implementation early create competitive advantages that become increasingly difficult for competitors to challenge.

The Implementation Framework for Organizational Success

Effective implementation begins with honest assessment of current AI initiatives against Strassmann’s operational versus managerial productivity criteria. Most organizations discover substantial skew toward managerial applications, which provides immediate clarity about disappointing results and clear direction for strategic redirection.

Establishing operational transformation as the primary criterion for AI investment approval requires organizational discipline and measurement rigor. This does not eliminate all managerial AI applications, which provide necessary support functions, but ensures that the majority of AI investment and attention focuses on initiatives that transform core business operations.

Developing industry-specific operational AI capabilities requires deeper investment and longer development cycles than implementing generic vendor solutions. However, this approach creates sustainable competitive advantages that generic solutions cannot match. Organizations achieving AI success build proprietary operational capabilities rather than simply implementing available tools.

Creating measurement systems that track operational transformation rather than efficiency gains alone requires sophisticated financial analysis linking AI initiatives to concrete business outcomes. Organizations must monitor revenue per employee growth, customer acquisition cost reduction, market share expansion, and competitive positioning changes to validate operational AI success.

The Choice That Defines Competitive Future

Every organization confronts the fundamental decision between using AI for management productivity enhancement or operational productivity transformation. While this choice appears subtle, the consequences prove profound and largely irreversible over competitive timescales.

Organizations that select the managerial productivity path experience modest efficiency gains that plateau relatively quickly. They achieve better reporting capabilities, faster analysis processes, and improved communication efficiency. Management teams feel more informed and productive. However, these improvements occur within existing competitive frameworks without fundamentally changing how the organization competes or creates value.

Organizations that pursue operational transformation experience entirely different trajectories. They reshape industry dynamics, capture disproportionate market share, and build competitive advantages that compound over time. The difference transcends degree to represent fundamental distinctions in competitive capability.

Paul Strassmann’s framework provides the analytical methodology for making this strategic choice intelligently. His extensive experience managing massive technology investments, rigorous analytical methodology, and demonstrated track record of delivering measurable results make his insights essential for contemporary AI strategy development.

The framework demands discipline in prioritizing long-term transformation over short-term convenience, measuring business outcomes rather than efficiency metrics alone, and pursuing operational transformation despite the apparent ease and safety of managerial applications. Organizations that embrace this challenge position themselves to define the next era of business competition.

The question facing organizational leaders is not whether to implement this framework, but whether implementation will occur before competitors gain insurmountable advantages. In the rapidly evolving AI landscape, this timing may determine competitive survival and success.

Sources

- Paul Strassmann – Information Science and Technology Colloquium Series, NASA GSFC

- Steve Jobs explains Paul Strassmann, Strassmann.com

- CIO Hall of Fame: Paul A. Strassmann, CIO Magazine, May 19, 2023

- Paul Strassman – Wikipedia, updated April 2025

- Why AI Is Not Getting The Spotlight During The Pandemic, Chief Executive Magazine, July 6, 2020

- Can generative AI overcome questions around scalability and cost? Goldman Sachs, December 16, 2024

- Paul Weiss Assessing Value of AI, But Not Yet on Bottom Line, Bloomberg Law, May 14, 2024

- Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence, Science Magazine

- The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier, McKinsey, June 14, 2023

- The Impact of Generative AI on Work Productivity, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, February 26, 2025

- AI Value Creators: Beyond the Generative AI User Mindset, Rob Thomas, Paul Zikopoulos, Kate Soule

Working with Claude “styles” to Conjure an Octopus

I’ve been tinkering with Anthropic’s optional writing styles in Claude to express a more creative, thought provoking, rather than definitive voice. I’m getting closer to what I want. Here’s an example, I’ve asked it to explain what an octopus is to someone who has never seen one.

Imagine if intelligence itself decided to abandon the tyranny of bones and instead embrace the fluid poetry of possibility. An octopus is nature’s meditation on what consciousness might become if freed from the rigid architecture that constrains terrestrial minds.

Picture a living liquid that has somehow learned to think—eight serpentine rivers of muscle flowing from a central bulbous sanctuary where cognition dwells. Each of these muscular streams can move with the independence of separate beings, yet remain unified in purpose, as if eight master calligraphers were drawing simultaneous verses of the same poem in three-dimensional space. These aren’t mere limbs but extensions of thought itself, each capable of tasting, touching, and exploring with a sensitivity that makes human fingertips seem crude by comparison.

The creature’s body defies our terrestrial logic of form following function. It can compress itself through any opening larger than its beak—the one rigid element in this symphony of softness—transforming from the size of a large dog to something that could slip through a keyhole. This shape-shifting isn’t mere contortion but a fundamental reimagining of what it means to have a body.

Most provocatively, this being has mastered the art of becoming invisible not through hiding, but through becoming. Its skin is a living canvas of chromatophores—cellular artists that paint reality in real-time, matching not just color but texture, transforming smooth flesh into coral, rock, or seaweed with the fluidity of thought itself. It doesn’t merely camouflage; it temporarily becomes whatever it observes, raising profound questions about the boundaries between self and environment.

Three hearts pump blue blood through this alien intelligence—redundancy that speaks to life’s determination to preserve such an extraordinary experiment in consciousness. Two serve the gills, one serves the body, and when it moves with sudden grace through its liquid realm, the central heart pauses, making every journey an act of biological courage.

What emerges is a paradox: a creature that embodies both ultimate vulnerability—having no protective shell or bones—and supreme adaptability. It suggests that perhaps the highest form of strength lies not in rigid defense but in infinite flexibility, not in maintaining form but in embracing transformation as the fundamental nature of existence itself.

How Corporations Maintain Their Core Identity While Adapting to Market Changes

Bottom Line Up Front: The most resilient corporations maintain organizational invariance by preserving their fundamental identity, core competencies, and strategic framework while adapting surface-level operations to dynamic market conditions. This principle explains why some companies thrive across multiple market cycles while others lose their way during periods of change.

The Strategic Paradox of Modern Business

Every business leader confronts the same fundamental paradox: how to adapt rapidly to changing market conditions without losing the core elements that created their organization’s success. This challenge has intensified as digital transformation, globalization, and accelerating consumer preferences create unprecedented rates of market change. Companies must simultaneously maintain their competitive identity while demonstrating the flexibility to evolve with their environment.

The corporate landscape provides stark evidence of this challenge. Technology giants that once dominated entire industries have disappeared within decades, not because they lacked resources or talent, but because they failed to balance adaptation with identity preservation. Conversely, certain organizations demonstrate remarkable longevity, maintaining their market relevance across multiple technological shifts, economic cycles, and competitive disruptions while preserving the essential characteristics that define their success.

This divergence in organizational outcomes reflects different approaches to managing change. Companies that struggle with adaptation often view change as requiring fundamental alterations to their identity, leading to strategic confusion and loss of competitive focus. Successful organizations approach change differently, maintaining clear distinctions between their essential characteristics and their tactical implementations.

The difference lies in understanding and applying organizational invariance, a principle from systems theory that explains how complex entities maintain their essential structure and identity while undergoing continuous internal change. This concept provides a sophisticated framework for understanding corporate resilience and strategic effectiveness in dynamic markets.

Understanding Organizational Invariance

Organizational invariance describes the preservation of fundamental characteristics that define a system’s identity, competitive advantage, and operational effectiveness, even as surface-level elements change continuously. In corporate contexts, this principle explains how successful companies maintain their core competencies, strategic frameworks, and cultural identity while adapting their products, services, market positioning, and operational methods to evolving conditions.

The concept differs fundamentally from static organizational stability, which would render companies inflexible and ultimately uncompetitive in dynamic markets. Instead, organizational invariance represents a sophisticated form of dynamic consistency where organizations preserve their essential patterns while enabling tactical flexibility in implementation. This approach allows companies to leverage their established strengths while responding effectively to new market realities.

Organizational invariance operates at multiple levels within corporations. At the strategic level, it preserves core competencies and competitive positioning frameworks that define how the organization creates value. At the operational level, it maintains decision-making processes, resource allocation patterns, and performance management systems that ensure consistent execution. At the cultural level, it preserves values, behavioral norms, and institutional knowledge that guide organizational responses to uncertainty and change.

The principle addresses a critical insight about sustainable competitive advantage: lasting success derives not from specific products, services, or market positions, but from the underlying organizational capabilities and patterns that generate consistent value creation across diverse market conditions. Companies that understand this distinction can adapt their surface-level activities while strengthening their fundamental competitive assets.

Mechanisms of Corporate Organizational Invariance

Successful corporations maintain organizational invariance through sophisticated mechanisms that operate simultaneously across different organizational levels and timeframes. These mechanisms work together to create institutional continuity while enabling strategic flexibility, ensuring that adaptation strengthens rather than compromises the organization’s essential characteristics.

Strategic decision-making frameworks serve as the primary mechanism for preserving organizational invariance during periods of change. These frameworks establish criteria for evaluating new opportunities, ensuring that strategic initiatives align with established corporate capabilities and identity. They function as institutional filters, enabling organizations to distinguish between opportunities that build upon their core strengths and those that might dilute their competitive focus. Effective frameworks incorporate both quantitative metrics and qualitative assessments that reflect the organization’s fundamental values and strategic priorities.

Cultural transmission systems preserve institutional knowledge, behavioral patterns, and organizational values that guide responses to market changes. Leadership development programs ensure that emerging executives understand and embody the organization’s essential characteristics while developing capabilities to navigate new challenges. Mentoring relationships transfer tacit knowledge about decision-making approaches, stakeholder management, and strategic thinking that cannot be captured in formal documentation. Knowledge management systems preserve critical insights about market dynamics, competitive positioning, and operational effectiveness that inform future strategic decisions.

Resource allocation processes direct investments toward activities that strengthen core competencies while enabling calculated exploration of adjacent opportunities. These processes prevent the dilution of organizational capabilities that occurs when companies spread resources too broadly in response to market pressures. Effective resource allocation maintains substantial investment in fundamental capabilities while dedicating specific portions of organizational resources to experimental initiatives that might extend existing competencies into new domains.

Information processing capabilities enable organizations to interpret market signals, competitive developments, and internal performance data through consistent analytical frameworks. These capabilities ensure that organizational learning builds upon existing knowledge rather than contradicting established strategic insights. They include market research methodologies, competitive intelligence systems, and performance measurement approaches that maintain analytical consistency while adapting to evolving information requirements.

Governance structures provide oversight mechanisms that monitor organizational coherence and strategic alignment during periods of significant change. Board composition, committee structures, and reporting relationships ensure that organizational invariance receives appropriate attention at the highest levels of corporate decision-making. These structures balance the need for strategic flexibility with requirements for maintaining institutional continuity and stakeholder confidence.

Dynamic Consistency in Practice

The most effective corporations achieve dynamic consistency by maintaining invariant organizational principles while allowing tactical flexibility in implementation. This approach enables companies to leverage their established strengths while adapting to new market realities, creating sustainable competitive advantages that persist across multiple business cycles and competitive challenges.

Netflix exemplifies dynamic consistency through its preservation of organizational invariance around data-driven decision making and customer experience optimization while transforming its business model multiple times. The company maintained its fundamental approach to understanding customer preferences through sophisticated analytics and recommendation systems while evolving from a DVD-by-mail service to a streaming platform and original content creator. The organization’s core competency in personalization technology and customer behavior analysis remained constant even as its revenue model, content strategy, and competitive positioning evolved dramatically.

The company’s invariant characteristics include its commitment to algorithmic content recommendation, its willingness to disrupt its own business model in response to technological change, and its focus on global scalability through technology platforms. These characteristics persisted through major strategic transitions, including the controversial decision to separate DVD and streaming services, the significant investment in original content production, and the expansion into international markets with localized content strategies.

Disney demonstrates similar principles by maintaining organizational invariance around family entertainment and storytelling excellence while expanding across diverse business segments and global markets. The company’s core competency in creating engaging content and memorable experiences transcends any specific delivery mechanism or market segment. Disney’s invariant characteristics include its commitment to high production values, its focus on emotional connection with audiences, and its systematic approach to brand extension across multiple revenue streams.

The organization has successfully adapted its storytelling capabilities to new technologies and market preferences while preserving the fundamental elements that define the Disney brand experience. This includes the transition from hand-drawn animation to computer-generated imagery, the expansion from animated films to live-action productions, and the development of streaming platforms that complement traditional theatrical releases. Throughout these changes, Disney maintained its organizational invariance around creative excellence and family-oriented entertainment values.

Amazon represents another compelling example of dynamic consistency through its preservation of organizational invariance around customer obsession and long-term thinking while diversifying across numerous business sectors. The company’s fundamental principles of customer-centric decision making, willingness to sacrifice short-term profits for long-term market position, and systematic approach to operational excellence have remained constant while the organization expanded from online book sales to cloud computing, logistics services, and artificial intelligence platforms.

Strategic Leadership and Organizational Identity

Corporate leaders play critical roles in preserving organizational invariance during periods of significant market change. Effective leadership requires sophisticated understanding of the organization’s essential characteristics and the ability to distinguish between fundamental capabilities and their temporary manifestations. This understanding enables leaders to guide strategic adaptation while maintaining institutional continuity and stakeholder confidence.

The most successful executives develop comprehensive frameworks for evaluating strategic opportunities against organizational invariance criteria. These frameworks consider how proposed initiatives align with existing competencies, whether they strengthen or dilute core capabilities, and how they contribute to long-term competitive positioning. Leaders use these frameworks to communicate strategic rationale to stakeholders, demonstrating how organizational changes build upon established strengths while addressing emerging market requirements.

Effective leadership during periods of market turbulence involves articulating clear connections between new initiatives and established organizational principles. Leaders must communicate how strategic adaptations represent evolution rather than fundamental transformation, maintaining employee confidence and stakeholder support during periods of significant operational adjustment. This communication requires deep understanding of organizational history, competitive positioning, and stakeholder expectations.

Change management approaches that preserve organizational invariance focus on reinforcing core capabilities while modifying their applications to new market conditions. Leaders emphasize continuity in organizational values and strategic principles while acknowledging the necessity of tactical adjustments. They frame strategic changes as natural extensions of existing capabilities rather than departures from established organizational identity.

Executive succession planning becomes particularly critical for maintaining organizational invariance across leadership transitions. Successful organizations develop leadership pipelines that ensure incoming executives understand and embody the organization’s essential characteristics while bringing fresh perspectives to strategic challenges. This approach prevents the discontinuity that often accompanies leadership changes in organizations that lack clear understanding of their invariant characteristics.