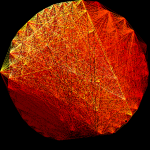

I always enjoy analyzing social networks (SN’s) that have had a lot less press than the Goliaths of MySpace and Facebook. I have done an awful lot of them, but one of my favorites was looking at the co-sponsorship patterns in the US Senate, 110th session (the current one).

This analysis was especially enjoyable because the graph is just one giant cluster, so conclusions took some real digging. So, what did we learn?

We learned a few things: graphs are just the beginning of analysis (but we knew that already); not all junior Senators are as strategic as others; and directionality of the relationships can have a large impact.

There are a handful of junior Senators setting themselves up for favor by strategically co-sponsoring specific bills. However, most junior Senators are building reputation by supporting anything that makes it to the floor. I am going to have to go back and analyze previous sessions to see which approach seems to provide the better payoff.

Relationships by-and-large are unequal between participants. Sometimes they are very close, sometimes they are very different. In our analysis of the Senate, many of these relationships are very unequal; a junior Senator is much more likely to co-sponsor a bill of a senior Senator than vice versa. Without bringing this inequality into play, our notion of network centrality is challenged. In this case, the two Senators most central include one first elected in 2004, followed closely by one who is a member of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee. If we view networks as expressions of influence over flow of information, including favors, that just doesn’t make sense.

When we start to bring directionality into consideration, which I did by splitting out the sponsors and co-sponsors for half of the Senate’s 104th session (1995); results become much more as expected. The most central Senator was John Warner, then president pro tem.